An edge-to-core strategy is essential when designing a city that enables digital capabilities to expand, enhance, and optimize traditional city infrastructure and services. Here are three principles to get you started.

Transforming a city’s digital capability and evolving its centralized IT applications and services requires the designers to adopt a nonlinear approach. You need new strategies, paradigms, and blueprints. You need to rethink how services are designed, where they are deployed, and how they capture data, as well as the process by which that data is turned into insights and actions.

Interaction with a city’s services and attractions should be fluid, immersive, contextual, personal, and efficient. An edge-to-core strategy can provide that.

In a city setting, think of the edge as a place, where actions and experiences happen. In an edge-to-core model, a digital architecture—the combination of technologies and smart services—is spread across the city. It should be designed to leverage data generated at the edge.

This article explores the following:

- What to consider when designing your city’s digital architecture

- Three key principles that can help inform decisions

- How data silos prevent the information-sharing required to deliver great city experiences

- The infrastructure and platforms—applications and services—that every city needs.

A digital infrastructure strategy: Begin with three key principles

The following principles can help you map out your strategy:

1. Act in context. You may want to optimize a city’s operations or deeply redesign the way people live. If so, you must understand what is happening and where, and identify and provide the right response to the uniquely contextualized situation.

2. Learn from real situations. Understand what can uniquely serve your residents—what features does your city need more than others? Observe and learn from real situations, then evolve infrastructure, processes, and services to support those needs. Public transportation services, for example, may be used differently than planned, so be mindful of emerging trends and plan accordingly.

3. Bring the digital and physical together. Ensure continuity of experience and tight, smooth integration between the physical city and its digital representation, as digitized services pair with traditional ones.

As an example of how to apply those three principles to a smart city challenge, let’s consider a recent workshop. Two dozen technologists from different smart city product areas were asked to find an unpredictable outcome. They were challenged to focus on possibilities rather than rely on legacy constraints and product limitations.

One of the use cases included how a city could leverage frames from a closed-circuit TV (CCTV) used for traffic control. At the end of the exercise, we concluded:

- The same information could be used to dim traffic lights when there were no cars, identify possible accidents, and locate potholes. This is acting in context.

- Recurring patterns as well as symptoms of specific situations, such as a car crash, could be derived from analysis of historical frames from a single CCTV, possibly with the help of artificial intelligence. This is learning from real situations.

- Physical actions, such as police intervention, might be required in certain situations. This is bringing the physical and virtual together.

Cross-silo cooperation benefits cities

The CCTV example provides two key lessons. First, adding one tightly focused silo after another around the same information does not provide an integrated, efficient system. Instead, you get just an array of silos. Second, you cannot predict how a single piece of information, such as a CCTV frame, can be used and by whom.

The workshop demonstrated that innovation is nonlinear and cannot be planned. Therefore, I recommend encouraging your team and partners to engage in unconstrained innovation and consider either dismantling silos or promoting cross-silo cooperation when possible.

If you then apply the three principles, it might look like this:

- Develop initiatives around a digital architecture, which is the overall design of your city. The goals should be to efficiently evolve and accommodate new data sources, services, and integrations. This is key to ensure short-term benefits in a longer-term executable strategy.

- A distributed digital infrastructure should cover the entire city, collect data from a growing number of sensors at a granular level, securely share data with multiple services, and operate immediately, as needed, upon events (acting in context).

- It should also digitally represent the physical world (physical and virtual together) while constantly adapting and evolving on the basis of the unique context (learning from real situations), collecting and elaborating data, and delivering digital services on one or more digital platforms.

Digital platforms every city needs

Once equipped with a digital infrastructure strategy, urban IT designers need to choose a digital platform. That is, you need a common software layer where services are implemented, deployed, and operated.

The digital platform is where you build the digital representation of the city and deploy smart services. The digital platform is at the core of the city, implicitly pairing with its administration, deployed in a city-owned data center or in the cloud.

In your city, you likely have one or more digital platforms. In fact, the market offers dozens of service platforms aimed at solving vertical problems or providing horizontal capabilities for several applications, such as smart traffic, smart lighting, or smart waste collection. However, none of them can realistically be the city platform. This reflects that technical, organizational, regulatory, or legacy constraints may force cities to create data silos. Nevertheless, innovation and real efficiency come when you leverage digital capabilities to break down silos’ walls.

Your digital architecture should consider two specific categories of platform capabilities:

- One category is about creating the digital representation of the city and learning from the real world (second and third principles). It provides data integration, aggregation of information from multiple sources, and dashboards, offering a mix of large datasets to artificial intelligence algorithms.

- The second category is where services are created and operated. You may have multiple platforms with different specializations (traffic control, water distribution, waste management). You may add a platform where developing and deploying services natively designed for integration (microservices) can be combined in a new value chain—extracting a frame from a CCTV and using for different purposes, for example. It is, again, a response to the second principle, relative to how executing digital actions have impact in the real world.

Edge and core: The city’s digital infrastructure

To act in context, you need digital capabilities as close as possible to where events happen, data is captured, and actions are taken. A “core” implementation, when data collected at the edge is sent to a data center or the cloud for processing, is not enough. It is physically far away from the city. Even the latest evolution of mobile connectivity (5G, low-power WAN, Wi-Fi, etc.) cannot quickly, efficiently, and sustainably transfer the massive amount of data generated by thousands of devices and sensors (i.e., waste bins, sprinklers, traffic lights, road signs, CCTVs) to the core platform(s) and back.

Therefore, you need a distributed digital infrastructure that brings a city’s connectivity, compute, storage, and services at the edge together with core platforms. The digital infrastructure enables cities to capture and store large amounts of raw data from sensors across the entire city for the longest possible time. Security and ease of access must be enabled. The design should meet the highly variable data speed, latency, and volume at city scale, scale over time to sustainably handle the explosion of sensors and data, and ensure consistent management of an extremely broad variety of devices.

In short, it has to capture data and information and move toward the platform(s) while keeping the process efficient.

The digital infrastructure enables cities to act in context (first principle). Data is not only captured but also elaborated, analyzed, eventually triggering needed actions or interacting with core services for further analysis. This happens “here and now,” without delays or service interruption. The amount of raw data should not have an impact on the action. This is an application of the Intelligent Edge paradigm.

In this way, the digital infrastructure is a multiplier of value rather than cost from the combination of different services, by providing a common shared data and service infrastructure for each context. Such distributed design is extremely flexible in terms of services and size.

This is also an application of the second principle (physical and digital together). Cities are designed by combining functions and spaces with infrastructures: The digital infrastructure is an intimate part of the city just as much as water and power distribution and roads are.

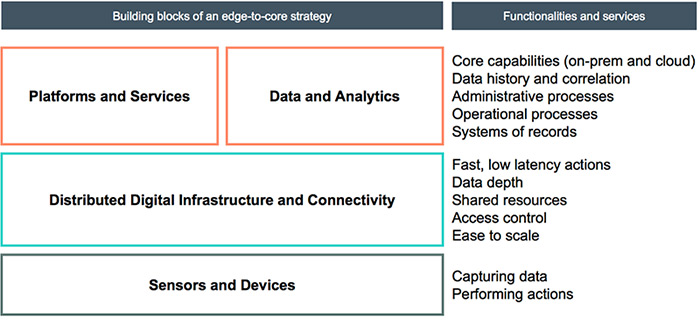

What the city’s digital blueprint might look like

Figure 1 shows an edge-to-core blueprint of a digital city. It includes one or likely more platforms, host services, and aggregate information at the core, in data centers or in the cloud, implementing the city’s systems of records.

A distributed digital infrastructure, overlapping other city infrastructures, brings connectivity, compute, and storage capabilities as well as service execution capabilities close to each context. Such proximity is key to accelerating event detection, processing, contextualization, and response, due to shortened distance and latency between detection and execution. You can scale and evolve your distributed edge nodes only where needed. A single event or frame captured by a sensor can be immediately made available to multiple applications, at the edge or at the core. Data is protected by moving only aggregated or metadata to the core while securely keeping raw data local. Resilience is increased by the high distribution of processing capabilities.

Sustainability is achieved by realizing the citywide digital infrastructure, distributing capabilities at the edge rather than having to expand an expensive wired or wireless backbone.

Figure 1. Edge-to-core blueprint

The edge-to-core design makes the city’s digital infrastructure a reality. It is just like other infrastructure—transportation, water, and waste—that pervasively enables interactions and relationships. The digital side of the city is an integrated, future-looking evolution of the city, pairing with and complementing the existing one, overlapping the city landscape and blurring with it.

Smart city digital strategy: Lessons for leaders

Three principles guide a smart city’s architectural strategy:

- An edge-to-core strategy, offering flexibility and outcomes that unleash nonlinear innovation opportunities.

- Doubling down on the edge, which enables full integration of digital services in smart cities.

- Technical and financial sustainability and scalability, enabled by a comprehensive digital architecture.

Destination url: http://hpe.to/6008DCZEM